Every sense we use to communicate with can be tricked, or confused into perceiving things that don't exist and not perceiving things that do exist. Our senses are good at what they do, but have limitations and adaptations that work for or against us in a certain way. If we know the limitations, we can better compensate using other techniques.

Optical Illusions

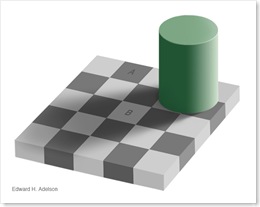

Take the image above for example. Are the squares A and B the same color, or are they different colors? They are the same color. Adelson of MIT explains the checker shadow illusion and why these appear to be different colors, but are in fact the same color. Both colors are the hex color code #777777. The visual system breaks down what it sees into components, allowing us to perceive the nature of what we see. In this case, assumptions on physical space and light lead us to a false conclusion.

In one study, at the Visual Cognition Lab at the University of Illinois, individuals were asked to count how many passes of a basketball were made by a specific team. Interestingly enough, about half failed to notice a gorilla that moves across the court and pounds it's chest.

Some key points on optical illusions (visual communication limitations):

- We see things that aren't there.

- We don't see things that are there.

- Focus or stress causes us to overlook things we would normally notice.

If our eyes can be deceived, then so can our other senses. When we try to communicate, we use written, visual, verbal, and nonverbal means to convey our message. Just like the optical illusion above, in every mode of communication there is the opportunity for illusions of communication to occur which can often lead to miscommunication.

Verbal Illusions

Speakers overestimate their effectiveness. I've known this from personal experience, but I wasn't aware of the significant degree of miscommunication that occurs. Experiments by Boaz Keysar and Anne Henly proved to me verbal illusions exist just as do optical illusions.

- Speakers are confident they are effective even if the information is ambiguous or unclear.

- Speakers are not understood as much as they think they are (less than ½ the time).

- Listeners are confident in understanding speakers

- Listeners do not understand as much as they think they do (less than ½ the time).

- Listeners are as confident when they are understanding correctly as when they misunderstand.

- Observers (not involved in the exchange) are more likely to identify potential misunderstandings.

- People that are anxious or depressed are more likely to incorrectly process ambiguous situations as threatening.

Written Illusions

Written communication can be even more prone to miscommunication. Ambiguity in verbal communications is even more detrimental to miscommunication in written form (e-mail, documents, requirements, etc.). Communication that takes place in written form is devoid of explanation, original intent, body language and inflexion that come with communication in person. Furthermore, most written communication tends to be viewed as more formal.

Think about it, if written communication were so easy and clear, why does the U.S. Constitution call for a panel of justices on the supreme Court to interpret the written laws?

Compensate for Illusions

We see things that aren't there, we don't see things that are. We think we hear things, clearly, but don't. No wonder software development projects fail. If we want to communicate better, what can we do?

When I was the chairman of the ActiveStore committee, I worked with team members from multiple companies in Europe, Asia, the Middle East, and the US. I learned that these senior people (presidents, vice presidents, directors) were good at communicating, but not immune from these illusions of communication. We would discuss a topic, come to a conclusion, reach an agreement, and then write it down. We found that only by using multiple avenues of communication (white boards, verbal, in-person meetings, and written summaries), did we actually agree on what we were trying to communicate.

I've since then worked with development and customer teams in four or five different physical locations, anywhere from 700 to 7000 miles apart. The problem only gets more complicated and complex the further the distance is involved. I've used the following points to help me communicate clearly.

- The burden of communication falls on the communicator.

- Assume only ½ of what is communicated is understood.

- Repeat important communication points multiple times in different ways.

- Don't be ambiguous, be specific.

- Have the recipient repeat what is understood.

- If something can be interpreted in multiple ways, clarify the original intent.

- Have the recipient state assumptions that are made.

Every instance that I have seen where there were significant gaps in what was expected versus what's been delivered in a software development project have all been preceded by little explanation, and large assumptions that were not clearly communicated. I've seen the above techniques clearing up communicating help improve understandings significantly.

References